Using Large Language Models for Patent Claim Mapping

— Patent — 43 min read

A few weeks ago, I released a patent search tool that automatically maps patent claims to prior art documents and ranks the matches. This post explains how the claim mapping component works - from training to evaluation to solving key problems like over-matching. You can try the tool at https://patent-prior.art/.

Introduction

Patent professionals need efficient ways to find and evaluate prior art that disclose claims. The tool I built helps automate this process. Using fine-tuned large language models, it achieves strong performance on patent claim mapping - improving from a 57/100 baseline score to 86/100 after training. This article explains the technical approaches that made this possible, starting with some background on patent claims and mapping.

Model Improvement Achieved

Scores on arbitrary 100-point scale (not percentages)

Background

A patent claim is a sentence that describes the "property" protected by the patent. Think of it like a property deed that marks the exact boundaries of what the patent owner "owns." Just as a property owner can exclude others from their land, a patent owner can exclude others from making, using or selling anything that falls within these claim boundaries.

What makes patent claims unique is their "all elements" rule: for something to infringe a patent claim, it must contain every single element (also called limitation) of that claim, either literally or through the doctrine of equivalents. If even one limitation is missing, there is no infringement. This fundamental principle shapes the entire practice of patent law. Unlike other potential systems that might protect broad concepts, pioneering work, or general technological areas, patent law focuses intensely on the technical language of claims themselves.

Consider the alternatives: We could have a system where infringement is found when one invention inspires another, or when someone was "first" in an area, or when an invention seems generally similar to what's claimed. Instead, patent law demands precise technical analysis of claim limitations. This precision means that working with patents requires meticulous attention to the specific boundaries defined by claim language—not just understanding the technical field, but understanding exactly what the claim language covers and doesn't cover.

This precise, limitation-by-limitation approach carries through to patent examination. For a patent to be valid, the claimed invention must not have been anticipated (already known to the public) or obvious to someone skilled in the field. When patent examiners evaluate applications, they must find prior publications that disclose or suggest every limitation of a claim. For each limitation, examiners provide specific citations showing where that limitation appears in prior art documents. This process—matching claim limitations to specific disclosures in prior art—is called patent mapping. It's fundamental to patent examination because it directly implements the "all elements" rule in determining whether an invention is truly new and non-obvious.

Patent mapping is a specialized task that requires deep technical understanding and reading comprehension. Recent advances in Large Language Models (LLMs) suggest they may be particularly well-suited for this type of work. These AI models have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in understanding technical and domain-specific language, including the ability to recognize when different phrasings express the same underlying concept. This semantic understanding, combined with their ability to process context and maintain logical consistency, aligns well with the fundamental requirements of patent mapping.

The practical feasibility of using LLMs for patent mapping has increased significantly with recent technological improvements. Modern LLMs can process much longer contexts - often 100,000 tokens or more - allowing them to analyze entire patent documents and prior art references in a single pass. These improvements in context length and reasoning capabilities, combined with decreasing costs per token, have transformed LLMs from an interesting research prospect into a practical tool for patent analysis.

While LLMs may not match the accuracy of experienced patent examiners, their significantly lower cost per document processed makes them an invaluable tool for augmenting human work. A single API call to process thousands of words of text costs mere cents, making it economically feasible to analyze large collections of prior art that might be prohibitively expensive to review manually. This cost advantage, combined with their technical capabilities, suggests that LLMs could significantly enhance the productivity of patent professionals while maintaining the precise, limitation-by-limitation analysis that patent law requires.

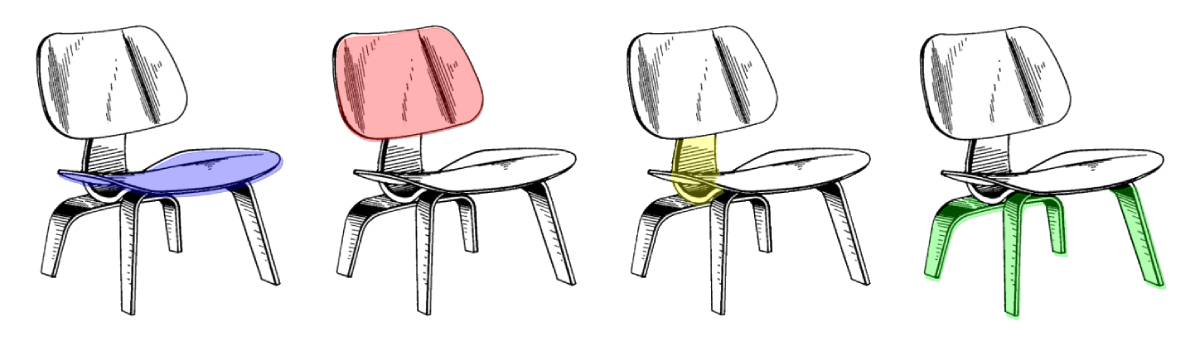

Illustration of What Mapping Is

Before we dive into how AI can help with patent mapping, let’s take a moment to consider how patent examiners perform this task. Patent examiners follow a systematic process when performing mapping. First, they break down the claim into its individual limitations. They then read and understand each limitation in the context of the full claim and any special definitions provided in the application. For each limitation, they analyze the prior art document to find matching disclosures, considering both explicit statements and inherent teachings. When they find a potential match, they must decide if it truly discloses the limitation and document the specific location that shows the disclosure. Examiners must keep in mind that applicants can be "their own lexicographers" - meaning they can define terms in their patent application to have specific meanings different from their ordinary usage.

Let’s look at example mapping of a claim to a chair to an imaginary patent disclosure. In the applet below, you will see the claim on the left, a patent disclosure on the right, and a figure from the patent disclosure on the bottom left. I’ve already mapped each limitation of the claim to locations in the disclosure and the figure. You can see each mapping by clicking on a limitation.

Diving Into the Problem

Identification of a Rich Data Source: patent application rejections

The patent examination process generates a wealth of publicly available data that can be harnessed to train LLMs for patent-related tasks. This project aims to utilize this data, particularly focusing on patent office actions, to create models capable of assisting in the evaluation of prior art and claims. The ultimate goal is to streamline the patent examination process, with a specific focus on responding to office actions and assessing the patentability of applications.

Patent office actions, especially those containing 102 and 103 rejections for anticipation and obviousness, serve as the primary source of data for this endeavor. These documents are invaluable as they typically contain the claims being examined, citations to relevant prior art, and explanations of how specific prior art references disclose or teach particular claim limitations. This structured format, where examiners map claim limitations to specific disclosures in prior art, provides an ideal foundation for training LLMs to perform similar tasks.

However, the utilization of office actions for training purposes presents several challenges. Examiners have the freedom to write rejections in any format they choose, leading to significant variability in structure and content. While a common format often includes separate sections for 102 and 103 rejections, with boilerplate language for legal requirements followed by claim-by-claim analyses, deviations from this structure are frequent. Examiners may combine multiple claims in a single rejection, rewrite claim language, summarize or generalize it, or modify it in various ways. Additionally, they may include brief excerpts or explanations alongside citations, or even incorporate annotated figures to illustrate their rejections.

Further complications arise from citations to non-patent literature, which can be difficult to obtain, and the inclusion of images, tables, or chemical formulas in claims, making the data challenging for LLMs to process. Citations to genetic sequences present another hurdle. Large numbers of citations per limitation can make it difficult to discern how the combined references disclose a particular element. Moreover, citations to extensive ranges, paragraphs, or figures can obscure the specific disclosure of a limitation. To address these challenges and create a standardized dataset suitable for training LLMs, I have opted to use LLMs themselves for data extraction and normalization. This approach involves using an LLM to process the original office actions and output a standardized format that captures the essential information in a consistent structure.

Basics of Training a Model to map claims

My approach to training models for patent claim mapping relies heavily on the strong base capabilities of current large language models while keeping the training process relatively straightforward. I started with models that already have excellent general language understanding, like those from OpenAI, which perform decently on the task even without specialized training.

The core prediction problems I aim to solve with this data are threefold: first, determining whether a particular document discloses a patent limitation, second, if it does, identifying where exactly the disclosure occurs, and, third, providing a human understandable reason for why a particular citation was chosen. These problems can be combined by prompting the model to either show where a limitation is disclosed and why, or state that it is not disclosed.

The training data comes from patent office actions, where I extract the claim, limitation, cited location, and an explanation. I also retrieve the prior art documents themselves. Each training example provides the description from a prior art document and shows the model how a patent examiner mapped a specific claim limitations to a location in a the document, along with their explanations for why those locations disclose the limitation. To provide useful context, I also provide the model the cited locations from previous limitations in the same claim.

The prompt I use for this task is shown below. Thus, the fundamental prediction task involves providing the model with a document, a claim, and a specific limitation, and having it predict either a disclosure location or respond with "Not Disclosed." This approach allows the model to simultaneously address both the existence of a disclosure and its location within the document. The disclosure location can be indicated in various ways, such as by repeating an excerpt of text from the relevant location or by providing a reference like a paragraph number or other inline location identifier. In our testing, I found inline location identifiers seemed to work best. As shown in the prompt, the model may also provide an explanation for each citation. I allow flexibility in how the model provides these explanations, matching how real patent examiners work. Sometimes they directly quote the prior art, sometimes they summarize what it teaches, and sometimes they describe which portion of the limitation is disclosed. While I could potentially improve results by requiring all three types of explanations, the current approach learns from and mimics actual examiner behavior.

Today you are going to act as a patent examiner. Your task is to review a claim, a limitation to examine from that claim, and prior work, and find additional disclosures in provided prior art.

To aid you in this task, we are providing prior art with tagged locations. You willidentify tags and tag location ranges that discloses the desired limitation. The prior art documentmay include issues introduced by a scanning process, try to determine the actual disclosure as best as possible. Here is the desired approach: First, describe some disclosure in the prior artthat reads on the limitation. Then, provide a location tag or location tag range(i.e, <LOCATIONX>-<LOCATIONY>) that provides the described disclosure. DO NOT PUT MULTIPLE TAGS OR TAG LOCATIONS ON A SINGLE LINE. You may use as many lines as needed to describe the disclosure. Seperate the disclosure and the locations tags with this seperator: -:-.

The description of the disclosure can be an excerpt from the prior art, a description of what the prior art teaches, a description of which portion of the limitation is taught by particular locations tags, orother information characterizing the disclosure. The "test" for a good description is "Does this description make it clear what locations in prior art disclose the limitation? Does it make clear if the location only teaches part of the limitation?"

When citing locations, disclosure text should be treated as belonging to the preceeding location identifier. For example, in this excerpt, "<LOCATION_10>[...] and a blue farbing, that <LOCATION_11> is attached to a[...]" we would say that "a blue farbing" is disclosed at <LOCATION_10>. It is possible that the element is not disclosed, so you may answer "<Not Disclosed>" in that case. It is possible that part of a limitation is disclosed and part is not.In such a case, describe what is not disclosed and tag it with "<Not Disclosed>" .

An example:

Claim:A writing implement comprising:an elongated outer casing having a longitudinal axis;a writing core disposed within the outer casing and extending along the longitudinal axis;a form-fitting, cylindrical sleeve composed of a woven or non-woven material, wherein the sleeve snugly surrounds and envelops the writing core;an adhesive material impregnating the sleeve, wherein the adhesive material, when set, forms a rigid support structure between the writing core and the outer casing.

Prior Art:<LOCATION_0>According to the present invention, the lead either in the form of a stick or a plastic mass, is provided with a covering or sheath of textile- is forced into the case, the sheath in accordtile fabric or other similar or suitable material ance with the present invention may first <LOCATION_1> be (0 treated by an adhesive which Sets ha to fitted within the case and fixed by an adhesive form a rigid or stifi support for the lead interand the marking substance then forced into posed between the latter and the case. Such position. The bore of the case, <LOCATION_2> whether the a sheath is readily cut away with the case to latter be made as a complete tube or in two expose the lead while at the same time it prohalves, may be corrugated 0r roughened the tects the latter during sharpening, writing more readily to hold the <LOCATION_3> glue and the sheath and against external blows, and supports in position. and retains the lead even should it fracture. It will readily be appreciated that a pen- Freferably the sheath is formed of textile cil constructed in accordance with my present 30 fabric such as cotton or linen, <LOCATION_4> which may if invention will be much less liable to breakage desired be of relatively coarse texture or looseof the lead whether during sharpening or due ly woven so as the more readily to absorb the to external blows. adhesive and retain a suitable quantity of it What I <LOCATION_5> claim is 7 when considerable pressure is applied to the In a marking pencil in which the marking 35 two halves of the case. substance is enclosed in an outer case capable In order that the method of applying such of being cut away to expose a portion of <LOCATION_6> the a sheath to the lead of a pc -cil may be more marking substance, the provision of a prefully understood, a pencil constructed in 210- formed tubular sheath of textile fabric drawn cordance with my present invention is illuson over the marking substance and impreg- 40 trated in <LOCATION_7> and described with reference to the ated with a hard setting adhesive to form accompanying drawings in which a stiff support for the marking substance Fig. 1 illustrates the method of sheathing interposed between the latter and the outer the lead or marking substance. case. <LOCATION_8>

Existing Work:"an elongated outer casing having a longitudinal axis"The bore of the case, whether the latter be made as a complete tube or in two halves, may be corrugated or roughened -:- <LOCATION_1>-<LOCATION_2>

"a writing core disposed within the outer casing and extending along the longitudinal axis"the lead either in the form of a stick or a plastic mass, is provided with a covering or sheath of textile- is forced into the case -:- <LOCATION_0>

"a form-fitting, cylindrical sleeve composed of a woven or non-woven material, wherein the sleeve snugly surrounds and envelops the writing core"the lead either in the form of a stick or a plastic mass, is provided with a covering or sheath of textile -:- <LOCATION_0>preferably the sheath is formed of textile fabric such as cotton or linen, which may if desired be of relatively coarse texture or loosely woven -:- <LOCATION_3>-<LOCATION_4>

Limitation to examine:an adhesive material impregnating the sleeve, wherein the adhesive material, when set, forms a rigid support structure between the writing core and the outer casing

Your response should be:the sheath ... may first be treated by an adhesive which sets to fited within the case and fixed by an adhesive form a rigid or stiff support for the lead and the marking substance then forced interposed between the latter and the case -:- <LOCATION_0>-<LOCATION_1>######

Ok, now your task:

Claim:{claim}

Prior Art:{prior_art}

Existing Work:{existing}

Limitation to Examine:{limitation}

Your work will be processed by a computer program, so please stick to the desired format or you will cause errors. Your response:Rather than trying to explicitly encode rules about what constitutes a valid disclosure or how to handle different levels of abstraction between claim language and prior art, I let the model learn these patterns from examples. The same applies to cases where multiple pieces of evidence need to be combined to fully disclose a limitation - while the model is permitted to cite multiple locations, as shown in the prompt, it learns how to do this primarily from seeing examples in the training data.

The output format, illustrated in the example within the prompt, is designed for reliable downstream processing, using a distinctive separator ("-:-") to clearly delineate between explanations and location tags. This formatting is taught through examples and explicit instructions rather than being hardcoded into the model.

This relatively hands-off training approach has several advantages: it's straightforward to implement, it naturally captures the nuances of how patent examiners work, and it maintains flexibility in handling diverse claim language and prior art disclosures. However, it comes with limitations: models can be too generous in finding mappings, may handle complex cases inconsistently, and I can't guarantee specific behaviors or standards. To address these limitations, additional filtering and verification steps are needed, which I discuss in the next section.

The need for an LLM Judge to Evaluate the Results

One of the fundamental challenges in evaluating LLM performance on patent mapping tasks is that there can be multiple equally valid locations within a document that disclose a given limitation. This makes it impossible to simply compare an LLM's output against an examiner's citation and score it based on exact matches.

To address this challenge, I developed an LLM judge system that could evaluate whether an LLM-provided disclosure was as effective as an examiner-provided disclosure. The judge uses the examiner citations as a gold standard against which the AI citations are compared against. The final output of the judge is score on a 100 point scale where 100 is an LLM citation that is as good as the human citation and 0 is an LLM citation that is incorrect.

Here’s the prompt:

You are an expert patent examiner tasked with evaluating the performance of an AI system in identifying relevant citations for patent claim limitations. Your role is to assess the quality of citations provided by the AI system compared to a reference provided by a human examiner for a particular claim limiation. You will use a specific scoring rubric to evaluate coverage, precision, and conciseness of the AI system citations.

Your task is to evaluate the AI system's performance in identifying relevant citations for a patent claim limitation. You will be provided with the following information:

1. The claim under examination2. previously examined limitation3. The patent claim limitation we are currently examining4. The human examiner's citations and explanations5. The AI system's citations and explanations

The human examiner and the AI systems include explanations that describe the human examiner and AI systems characterization of their citation,along with the actual excerpt cited. You should treat the explanations as describing reasoning (that may be flawed) and not as a correctdescription of the citations.

Please follow these steps in your evaluation:

Limitation Breakdown:Analyze the given limitation in light of the previously examined limitations, and the examiner and AI's citations. Break the limitation downinto key components or concepts. Briefly explain your breakdown.

Citation Analysis:For both the human examiner's and AI system's citations:a) Identify which components of the limitation each citation coversb) Assess the relevance and completeness of the disclosure for each componentc) consider how the previously examined limitations interact with the citations to teach the limitation

* A NOTE ON CITATION FORMAT* - For this task, the important citations are "<LOCATION_X>" tags. Normal citations approaches, such as figures,paragraphs, line numbers, etc. may be referenced by both the examiner and the LLM but are less relevant for this task. Again, in this task, weare measuring the quality of the text as indicated by citations to "<LOCATION_X>" tags.

You should presume that the human examiner has identified citations that fully disclose the limitation (unless clearly deficient). The analysis of human examiner's work is to understand best practices for use in judging the AI system's work, as the goal for the AI system is not some abstract form of perfection but to reach a level comparable to the human examiner.

Both the human examiner and/or the AI system may assert that the limitation is not disclosed. This will be indicated with "<Not Disclosed>".When encountering "Not Disclosed" by just one of the human examiner or AI, you should consider whether there are valid reasons for disagreement that may suggest awarding points, but, generally, a disagreement suggests a 0 point final evaluation.

Comparative Analysis:Compare the AI system's work to the human examiner's work. Analyze differences in coverage, precision, and conciseness. All textual analysisfor those components should be placed in this section, including all analysis for scoring, leaving the "Scoring" and "Final Evaluation" sectionsreserved strictly for numbers for the automated computer score calculations.

Scoring:This section is reserved solely for reporting score numbers in the shown categories. All analysis should be done in the comparative analysis.Use the following rubric to score the AI system's citations:Coverage (60 points):

Full coverage matching or exceeding the human examiner's citations: 60 pointsPartial coverage:

If human examiner has N cited locations, each location is worth (60 / N) pointsAward points for each examiner location that the AI successfully covers

No coverage matching the human examiner's citations: 0 pointsIf AI provides better coverage than the human examiner: Still award full 60 points

Precision (30 points):

Citations are clearly on point and as good as or better than the examiner's: 30 points

If human examiner has N cited locations, each location is worth (30 / N) points

At least, for each citation that is less relevant or clear than the examiner's: -5 points or moreFor each redundant citation: -5 points or more

Conciseness (10 points):

AI provides concise, non-redundant citations: 10 pointsSlight verbosity or minor redundancies: 5 pointsSignificant verbosity or many redundancies: 0 points

Final Evaluation:Provide a numerical score for the AI system, summarizing Coverage, Precision, and Conciseness. The score should be between 0 and 100. This section is reserved solely for reporting the final numerical score. When the coverage is really poor it can be appropriate to havelow or zero scores for Precision and Conciseness.

Please present your evaluation strictly in the following format:

### Limitation Breakdown:[Your breakdown of the limitation into key components]

### Citation Analysis:#### Human Examiner:[Analysis of each human examiner citation]

#### AI System:[Analysis of each AI system citation]

### Comparative Analysis:[Your analysis comparing the AI system's performance compared to the human examiner's reference, all remaining textual analysis must go here]

### Scoring:Coverage: [Score]/60Precision: [Score]/30Conciseness: [Score]/10

### Final Evaluation:[Numerical score - between 0 and 100]

Remember, the AI system may find valid citation locations not identified by the human examiner. Consider these as potentially valuable insights rather than errors, as long as they are relevant and non-redundant. The AI system can receive full points (but no more than 100) if it performs better than the human examiner.

Task Information:Claim:{claim}

Previously Examined Limitations:{previous_limitations}

Current Limitation we are examining:{current_limitation}

Human Examiner Citations:{human_citations}

AI citations:{ai_citations}

Please proceed with your evaluation based on this information.Let’s break down how the judge works. First, to better ground the comparison, the judge is prompted to employ a chain-of-thought evaluation. The evaluation is structured to encourage well considered evaluations. Based on the evaluation, the judge constructs a score based on a rubric that awards points in coverage, precision, and conciseness. The judge then provides a final score.

As context for the evaluation, we provide the judge with the complete patent claim, any previously examined limitations, and the specific limitation under review. The judge first breaks down the limitation under examination into key components or concepts and is instructed to analyze its components in light of the previously examined limitations, the examiner’s citations and the LLM citations. Then, the judge performs a citation analysis for both the human examiner's and AI system's citations to identify which components of the limitation each citation covers, assess the relevance and completeness of the disclosure for each component, and consider how the previously examined limitations interact with the citations to teach the limitation. Finally, the judge is prompted to perform a comparative analysis comparing the LLM citations to the human citations and analyze differences in coverage, precision, and conciseness.

A numerical score summarizes the evaluation. The scoring methodology uses a 100-point system that weights different aspects of citation quality. Coverage accounts for 60% of the total score and measures how completely the citations address all components of the limitation. Precision contributes 30% and evaluates the relevance and clarity of the citations. The final 10% is allocated to conciseness, rewarding efficient citation sets that avoid redundancy.

This evaluation process for the judge prompt is admittedly ad hoc. It was developed iteratively as I tried find a way to guide the judge LLM to decent performance on the task. Noticeably, it is not strongly tied to legal standards or how an examiner might describe the task. During development, I found that adding instructions that referred to legal standards or patent terms of art would frequently reduce observed performance on the task as it would induce the model to talk more like a lawyer rather than to do the task. Conversely, I found that adding instructions that dealt with edge cases that would cause the LLM to be wrong were very helpful in improving performance. The end result, then, is a prompt that is very much a kludge–far from perfect, but it works well enough that progress could be made.

I fine-tuned a model on the judge task to improve performance. To create the dataset, I manually filtered and hand-edited the output of an untrained model to create examples of judge output to show the desired evaluation and scoring approach. Using this approach I was able to collect 56 examples for training the judge model.

To evaluate the fine-tuned judge, I manually reviewed 90 outputs from the fine-tuned judge model. I found very few obvious errors, but the outputs spanned many different fields that I have little expertise in, so I could not fully judge the output. Proper evaluation of the judge would require manual review by subject matter experts across many technical fields.

Using the LLM judge as an evaluation metric, our base model gpt-4o mini (specifically, "gpt-4o-mini-2024-07-18") achieved a score of 57 out of 100, while our best fine-tuned model reached 86 out of 100. (The judge scores are qualitative on an arbitrary scale out of 100 and should not be viewed as a percentage.)

Model Performance Comparison

Scores on arbitrary 100-point scale (not percentages)

Improving Mapping Quality through Scoring and Filtering

A fundamental challenge I encountered with LLM-based patent mapping is models finding lots of low quality mappings. I believe this problem stems from the nature of our training data. Since I derived the training examples from examiner rejections, the prior art documents in our dataset are inherently pre-selected for their relevance to the claims they're being mapped against. This creates a distribution heavily skewed toward positive matches that doesn't reflect the reality of analyzing search results, where many documents may be only tangentially related to the claimed invention. While the ideal solution would be to create a balanced dataset by manually labeling random prior art documents for disclosure, the cost of such annotation would be prohibitive.

However, to solve this problem, we can leverage a source of negative examples within examiner rejections themselves. When examiners issue rejections under 35 USC 103 for obviousness, they frequently identify limitations that are not disclosed in particular references – after all, the very nature of an obviousness rejection implies that at least one reference fails to disclose all limitations of the claim. By systematically extracting these cases across many applications, we can build a dataset of documents known not to disclose specific claim limitations.

Using this insight, I created a specialized filtering/scoring LLM that evaluates how well the proposed mapping actually discloses the limitation. This scoring model is trained on a balanced dataset combining positive examples from examiner citations and negative examples extracted from 103 rejections, providing a more realistic assessment of disclosure likelihood.

The scoring model employs the prompt shown below to frame the task from the perspective of an experienced patent examiner. This prompt guides the model to evaluate disclosure on a 0-100 scale while considering multiple critical factors: relevant rules of claim construction, the level of skill of a person of ordinary skill in the art, the target limitation in light of the entire claim, potential ambiguities in the prior art document, and doctrines that might affect likelihood of disclosure. Importantly, the prompt acknowledges that the prior art excerpts being evaluated were selected by an imperfect system and encourages consideration of what might appear elsewhere in the document.

You are an experienced patent examiner tasked with analyzing patent claims and prior art documents. Your goal is to determine the likelihood that a given prior art document discloses a specific limitation from a patent claim.Task:

1. You will be provided with:a) A patent claimb) A target limitation from that claimc) Excerpts from a prior art document

2. Analyze the excerpts and estimate the likelihood that the document discloses the target limitation from the claim.

3. Perform a detailed analysis considering the following:

- Relevant rules of claim construction- The level of skill of a person of ordinary skill in the art- The target limitation in light of the entire claim- Potential ambiguities in the prior art document- Doctrines that might increase the likelihood of the limitation being taught- Possible content in the rest of the document, beyond the provided excerpt

4. After your analysis, provide a "Final Score" from 0 to 100 in the following format:Final Score: [number from 0 to 100]

Where:- 0 means the prior art document does not disclose the limitation- 100 means the prior art document definitely discloses the limitation- Intermediate numbers express degrees of uncertainty

Consider how various factors might increase or decrease the score by tens of points, providing a fine-grained estimate.

Important considerations:

The prior art document may not be directly relevant to the claim.The excerpt is chosen by another system to be the closest to teaching the limitation, but this system is imperfect.You will be evaluated based on whether the limitation is taught anywhere in the full document, not just in the excerpt.You may extrapolate what might be in the rest of the document when making your prediction.

Before you begin your analysis, recall relevant patent examination rules and claim construction principles. Apply these to the specific case at hand.Examples:

Example 0:

Patent claim:1. A method, comprising: supplying water for a mud mixture to a mixing tank according to a predetermined volume; supplying, using a rheological sensor, a viscosifier to the mud mixture in the mixing tank until the mud mixture achieves one or more predetermined rheological values; supplying, using a density sensor, a weighting agent to the mud mixture in the mixing tank until the mud mixture achieves a predetermined specific gravity value; and supplying, using a pH sensor, a buffering agent to the mud mixture in the mixing tank until the mud mixture achieves a predetermined pH value to produce a drilling fluid.

Limitation:use of a buffering agent to achieve a predetermined pH

Prior Art Excerpts from a document that teaches the limitation:

Location 0:In other aspects, the component may refer to any substance or material added to the fluid as an additive or in order to treat the fluid or the flow path. For instance, the component may include, but is not limited to, acids, acid-generating compounds, bases, base-generating compounds, biocides, surfactants, scale inhibitors, corrosion inhibitors, gelling agents, crosslinking agents, anti-sludging agents, foaming agents, defoaming agents, antifoam agents, emulsifying agents and emulsifiers, de-emulsifying agents, iron control agents, proppants or other particulates, gravel, particulate diverters, salts, fluid loss control additives, gases, catalysts, clay control agents, clay stabilizers, clay inhibitors, chelating agents, corrosion inhibitors, dispersants, flocculants, base fluids (e.g., water, brines, oils), scavengers (e.g., H 2 S scavengers, CO 2 scavengers or O 2 scavengers), lubricants, breakers, delayed release breakers, friction reducers, bridging agents, viscosifiers, thinners, high-heat polymers, tar treatments, weighting agents or materials (e.g., barite, etc.), solubilizers, rheology control agents, viscosity modifiers, pH control agents (e.g., buffers), hydrate inhibitors, relative permeability modifiers, diverting agents, consolidating agents, fibrous materials, bactericides, tracers, probes, nanoparticles, and the like. Combinations of these substances can be referred to as a substance as well.

Prior Art Excerpts from a document that does not teach the limitation:

Location 0:In some embodiments, the integrated fluids system 100 may control the operation of the mixing system 200, the dry additive system 300, the liquid additive system 400, and the pumping system 700. Based on the data collected by the control unit, the control system 600 may modify the mud composition or the cement composition. The control system 600 may also control when the integrated fluids system 100 switches from pumping mud to pumping cement. The control system 600 may also control the cleaning system 800 such that the integrated fluids system 100 is cleaned when switching between mud and cement operations.-------

Example 1:

Patent claim:1. A method comprising : receiving an indication of a data source; retrieving a page corresponding to the data source, wherein the page corresponds to a first user account for the data source; outputting for display a request to indicate a page context of the page; retrieving a plurality of tasks corresponding to the page context; outputting for display a plurality of requests corresponding to the plurality of tasks; recording user input corresponding to the plurality of tasks; generating, based on the user input and the plurality of tasks, a set of structured data corresponding to the data source; and retrieving, based on the set of structured data, data from the data source, wherein the data corresponds to a second user account for the data source.

Limitation:retrieving, based on the set of structured data, data from the data source, wherein the data corresponds to a second user account for the data source

Prior Art Excerpts from a document that teaches the limitation:

Location 0:At 604, the SRM system may retrieve client profile data associated with the borrower, based at least in part on the borrower identifier. The client profile data may include one or more relationship attributes that describe observable characteristics of the borrower's relationship with a financial institution. Alternatively, the SRM system may retrieve the one or more relationship attributes from a relationship attribute repository native to the SRM system, based at least in part on the borrower identifier.

Prior Art Excerpts from a document that does not teach the limitation:

Location 0:The system memory 906 may include various types of computer-readable storage media in the form of one or more higher speed memory units, such as read-only memory (ROM), random-access memory (RAM), dynamic RAM (DRAM), Double-Data-Rate DRAM (DDRAM), synchronous DRAM (SDRAM), static RAM (SRAM), programmable ROM (PROM), erasable programmable ROM (EPROM), electrically erasable programmable ROM (EEPROM), flash memory (e.g., one or more flash arrays), polymer memory such as ferroelectric polymer memory, ovonic memory, phase change or ferroelectric memory, silicon-oxide-nitride-oxide-silicon (SONOS) memory, magnetic or optical cards, an array of devices such as Redundant Array of Independent Disks (RAID) drives, solid state memory devices (e.g., USB memory, solid state drives (SSD) and any other type of storage media suitable for storing information. In the illustrated embodiment shown in FIG. 9, the system memory 906 can include non-volatile memory 910 and/or volatile memory 912. A basic input/output system (BIOS) can be stored in the non-volatile memory 910.-------

Example 2:

Patent claim:1. A package structure, comprising: a substrate disposed with a solid grounded copper layer on a surface layer; at least two radio frequency chip modules disposed on the substrate; a plastic encapsulation disposed on the substrate and coating the at least two radio frequency chip modules; a groove penetrating an upper surface and a lower surface of the plastic encapsulation and located between the adjacent two radio frequency chip modules; a solder filling body filled in the groove; and a shielding layer covered on the upper surface and lateral surfaces of the plastic encapsulation, an upper surface of the solder filling body and lateral surfaces of the substrate; wherein the solid grounded copper layer corresponds to a bottom surface of the groove, and makes contact with the solder filling body.

Limitation:a solid grounded copper layer

Prior Art Excerpts from a document that teaches the limitation:

Location 0:Referring again to FIG. 2, to electrically interconnect the control logic dies 206 and the transducers 212, in an embodiment, the flexible substrate 214 further includes conductive traces 216, 217 formed on the film layer or under the film layer inside the lumen 238 that carry signals between the control logic dies 206 and the transducers 212. In particular, the conductive traces 216 providing communication between the control logic dies 206 and the transducers 212 extend along the flexible substrate 214 within the transition region 210. In some instances, in the region 208, conductive traces 217 can facilitate electrical communication between the master controller 206 A and the slave controllers 206 B. The conductive traces 217 can also provide a set of conductive pads that contact the conductors 218 of cable 112 when the conductors 218 of the cable 112 are mechanically and electrically coupled to the flexible substrate 214. Suitable materials for the conductive traces 216, 217 include copper, gold, aluminum, silver, tantalum, nickel, and tin, and may be deposited on the flexible substrate 214 by processes such as sputtering, plating, and etching. In an embodiment, the flexible substrate 214 includes a chromium adhesion layer. The width and thickness of the conductive traces 216, 217 are selected to provide proper conductivity and resilience when the flexible substrate 214 is rolled. In that regard, an exemplary range for the thickness of a conductive trace 216, 217 and/or conductive pad is between 10-50 μm. For example, in an embodiment, 20 μm conductive traces 216, 217 are separated by 20 μm of space. The width of a conductive trace 216, 217 on the flexible substrate 214 may be further determined by the width of the conductor 218 to be coupled to the trace/pad. In some examples, in place of the conductive traces, conductive traces 216 are formed on top the film layer of the flexible substrate 214.

Prior Art Excerpts from a document that does not teach the limitation:

Location 0:As illustrated in FIGS. 1A and 1B, the semiconductor device structure 100 includes a substrate 110; an electronic component 120 A, such as an electronic die 120 A or semiconductor die 120 A; an electronic component 120 B, such as an electronic die 120 B or a semiconductor die 120 B; a first shielding structure 130 or an internal shielding structure 130; a package body 140 or an encapsulant 140; and a second shielding structure 150 or a shielding layer 150. In the present embodiment, the semiconductor die 120 A and the semiconductor die 120 B are attached to a first major surface of the substrate 110, and are laterally spaced-apart from each other. In other embodiments, another semiconductor die or electronic component can be stacked on top of one more of the semiconductor die 120 A or the semiconductor die 120 B. In some embodiments, the semiconductor device 100 can further include at least one external interconnection structure 160 attached to a second major surface of the substrate 110. In accordance with the present embodiment, the internal shielding structure 130 comprises a plurality of conductive spaced-apart pillar structures 131 encapsulated within package body 40 as generally illustrated in FIG. 1A. According to the present embodiment, the conductive spaced-apart pillar structures are attached to the substrate 110 at one end only, and the opposite end is spaced apart from the substrate 110 as generally illustrated in FIG. 1A. In some embodiments, the conductive spaced-apart pillar structures 131 are vertical conductive wires or vertical wires with one end attached to the substrate 110 and the opposite end detached from the substrate 110.-------

Example 3:

Patent claim:21. (New) A method for bridging and assigning specific users' personal data contained on communications devices and social networking services with user associated contacts at the onset of a telephony interaction, the method comprising: receiving, from a first user, a first selection of data destined for a second user, the first selection being made on a selection interface screen of a remote application on a device associated with the first user; sending the first selection of data to a device associated with the second user, the first selection of data being presentable on the device associated with the second user in connection with a telephony interaction initiated by the first user to the second user on the device associated therewith; matching, based upon the designation of the second user by the first user, a user account on a remote service associated with the second user; retrieving, based upon the matching of the second user to the corresponding user account on the remote service, a second selection of data of the second user from a collection of data dynamically defined thereby; scoring the second selection of data of the second user; selectively sending the second selection of data to the first user based upon the scoring thereof, the second selection of data being presentable to the first user in connection with a telephony interaction initiated by the second user to the first user; associating the second selection of data sent to the first user as inbound visual data, and the first selection of data as outbound visual data, each for an entry in a listing of names corresponding to the second user; and displaying the entry corresponding the second user on a listing of names on a contacts interface screen, a reduced representation of the inbound visual data and a reduced representation of the outbound visual data being displayed in respective, adjacently positioned columns; wherein the telephony interactions are voice calls.

Limitation:scoring the second selection of data of the second user

Prior Art Excerpts from a document that teaches the limitation:

Location 0:In an alternate embodiment, the routing and destination data included in a stored template in the database 115 may call for a social stream to be rated for content relevancy and sentiment of the author. Here, the NLU engine 125 will parse the data, create a sentiment, and relevancy score, and embed all of the requisite scoring information into the item. In a preferred embodiment of the invention, the authors' posts may be related in such a way as to provide the agent with scoring data to forecast the likelihood of the post being “spam.” Likewise, data tagged with sentiment by the NLU engine 125 may be used to prioritize the routing and disposition of a social item.Location 1:At a decision branch 1075, the application server 110 queries the CRM customer data 310, 410, via the enterprise data access point 160. In a preferred embodiment of the invention, the enterprise data access point 160 will have direct access to the CRM customer data 310, 410. In an alternate embodiment, the enterprise data access point 160 will have access to the CRM Customer data 310, 410 via the agent interface 305, 405. The purpose of the query is to ascertain the availability of relevant customer data that can be matched with the social data. For example, customer value score data, recent buying history data, or trouble ticket data. Such data is then matched by the application server 110 with the rules engine 120 to determine if any pre-set rules will govern agent next best actions or agent display attributes. If no data is available, the process moves to updating the agent interface 305. 405 with available data.

Prior Art Excerpts from a document that does not teach the limitation:

Location 0:It is noted that in various embodiments the present invention may relate to processes such as are described or illustrated herein and/or in the related applications. These processed may be implemented on the host system 140 on one or more host system servers 370 by one or more host system application 364, as well as one or more portable devices 110 by one or more client applications 264. These processes are typically implemented in one or more modules comprising systems as described herein and/or in the related applications, and such modules may include computer software stored on a computer readable medium including instructions configured to be executed by one or more processors. It is further noted that, while the processes described and illustrated herein and/or in the related applications may include particular stages, it is apparent that other processes including fewer, more, or different stages than those described and shown are also within the spirit and scope of the present invention. Accordingly, the processes shown herein and in the related applications are provided for purposes of illustration, not limitation.Location 1:In a similar fashion, updated user information for a particular contact and may be synchronized with and transmitted to other users or contacts by host system 140. For example, when a first user updates his or her information in this fashion, their updated information may be sent by host system 140 to all of the first user's contacts on the contacts' associated devices 110. Similarly, host system 140 may poll or otherwise periodically check the contact information and status for various users of the host system 140, update their information in the database 390, and/or transmit that updated information to other user's that may be contacts or otherwise have a connection with the polled user.-------

Each example above includes:

- A patent claim- A target limitation from that claim- An excerpt from a prior art document that another examiner found teaches the limitation- An excerpt from a prior art document that another examiner found does not teach the limitation

Now, proceed with your analysis of the provided claim, limitation, and prior art excerpts. Provide detailed reasoning before giving your Final Score.

Patent claim:{claim}

Limitation:{limitation}

Prior Art Excerpts: {excerpt}To ground the model's evaluation, the prompt includes complete examples spanning different technical domains, each containing both positive and negative cases. While these examples weren't extensively optimized, they provide reference points for the model to understand the task.

In the search app, the scoring model's output can be translated into practical categories for users. For example, scores below 50 can be labeled "Not likely disclosed," 50-75 labeled as "Possibly disclosed," and scores above 75 might be considered "Likely disclosed." While I came to these thresholds through observation rather than rigorous validation, they provide an intuitive framework for users to understand the results. The app presents these categories through color coding while also displaying the specific citation location and the model's explanation for why it believes the limitation is or isn't disclosed.

Model Confidence Categories

Not likely disclosed

0-50%Possibly Disclosed

50-75%Likely Disclosed

75-100%Color Coded Confidence Categories (say that five times fast)

This filtering approach represents a practical solution to the over-matching problem, but several areas for improvement remain. The scoring thresholds could benefit from more rigorous validation, the example set in the prompt could be optimized, and the presentation of results could potentially be refined based on user workflow patterns. Nevertheless, the current implementation provides a valuable tool for reducing false positives while still capturing legitimate disclosures of claim limitations in prior art documents.

Conclusion

Language models can perform well on challenging tasks like patent mapping. Through careful training, evaluation, and filtering, I achieved an 86/100 score on mapping accuracy. While this technology isn't good enough to replace patent professionals, it can help them work more efficiently by automating the tedious parts of prior art search and analysis.

Try it yourself at patent-prior.art. Submit a claim and priority date, and you'll receive a detailed analysis within 24 hours. I'm actively developing new features and welcome feedback - reach out on X @niemerg.